Understanding the role of government

|

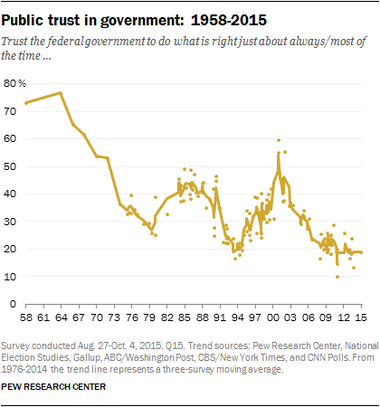

It's important to note that public trust in government is near historic lows, according to Pew Research.

The increasing mistrust of government isn't baseless. Government has garnered a reputation as a "revolving door" in which people from the private sector-- the coal industry-- find themselves in government positions, or vice versa. Indeed, it's difficult to determine the exact number of "revolving door" personnel, the amount of all political campaign contributions (undisclosed contributions included), or the effectiveness of lobbying dollars that is poured into the political machinery that keeps coal afloat. This is not to mention the investments that Senators and Congress members have in coal and related industries. These apparent conflicts of interest cross party lines, and undoubtedly serve to foster public mistrust in government. |

Retracing our steps

|

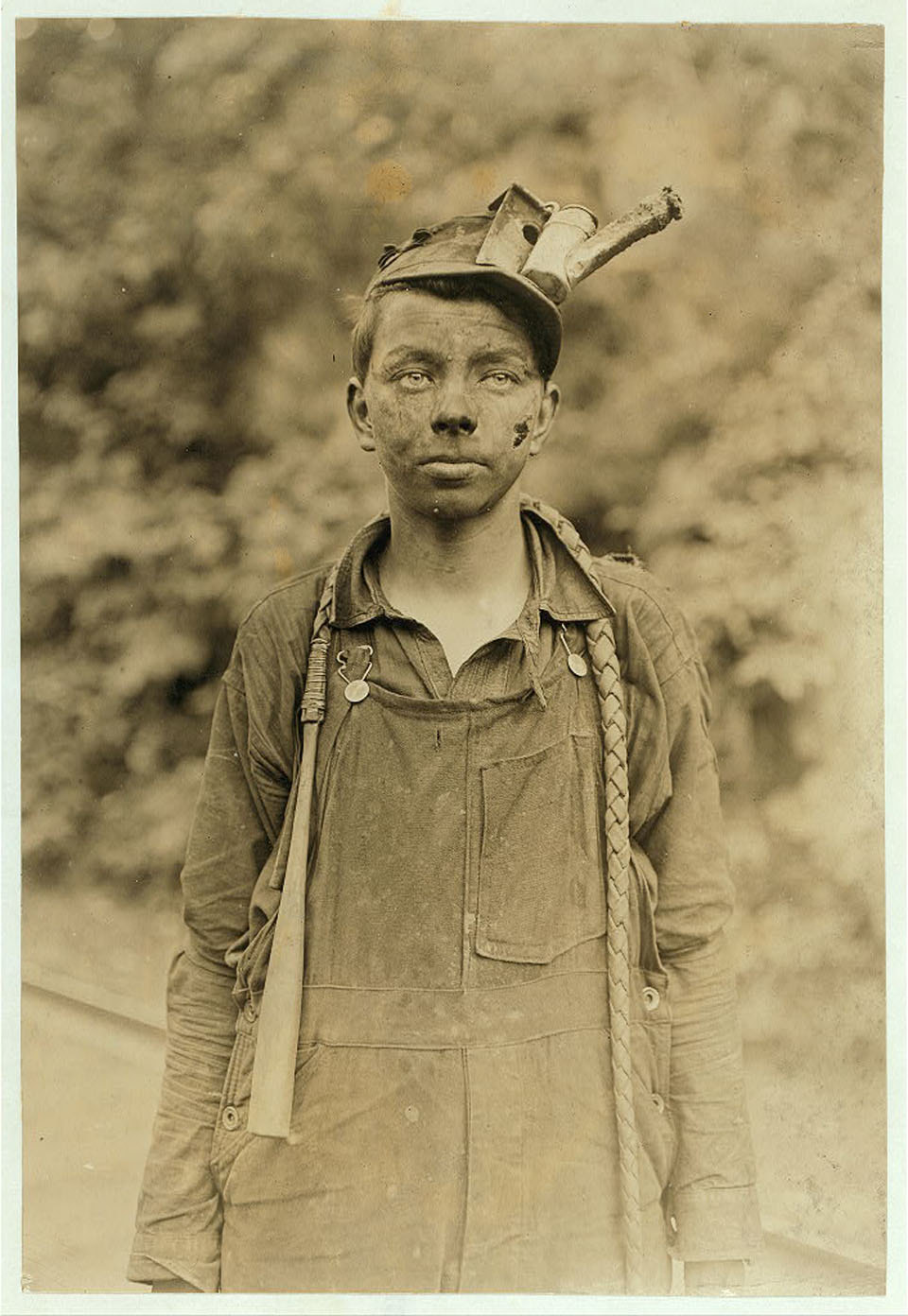

Not only was government intervention against coal miners a problem, but the ineffective enforcement of mining laws was also a major issue. Child labor laws began to be enacted in the mid 1890s with a Pennsylvania law that forbade employment of anyone under the age of 12 from working in a coal mine. Lack of enforcement meant that many employers got away with forging documentation. It was only in the 1910s that the number of children working in coal mines began to drop, mostly because of technological improvements. By 1920, child labor in mines was virtually nonexistent because of the efforts of individuals and groups that educated the public on children working in mines.

Coal industry subsidies began in 1932 as the federal government permitted companies to deduct some of their income. Since 1950, the government has handed the coal industry more than $70 billion in tax breaks and subsidies (adjusted for inflation). [source] |

How did coal get to be such a power player in the world of politics?

A look at history, especially in the last century, reveals strong ties between the coal barons of yesteryear and those in the political sphere. Coal companies relied on government to provide support in breaking up strikes. In Morewood, Pennsylvania in 1891 miners were striking for higher wages and an 8-hour workday. Deputized National Guard members fired into the crowd of strikers, killing 6. Later, in 1903, an armed posse of 30 led by federal, county and labor detectives conducted a dawn raid in a house full of strikers in Stanaford, West Virginia, killing 3. Another 3 were also killed in related violence.

|

Smokescreens

The coal industry has long held that they are very concerned with protecting jobs. Their opposition to any laws that might affect their bottom line is nearly universally couched in terms of the number of jobs that would allegedly be lost. Political supporters frequently mimic this rhetoric, diminishing coal workers to pawns in their quest to accomplish what is most politically (and financially) expedient.

The coal industry and its political allies create a smokescreen that does nothing to "protect" jobs. The continuous failure of the coal industry to follow basic laws that protect workers and the environment clearly demonstrates where their priorities lie.

Let's go back to mine safety for a moment. On December 6, 1907, at 10:28 AM, approximately 367 men in two mines were killed in an explosion thought to be caused by either an electrical spark or an open flame lamp that ignited coal dust in the air. Up to that point, there hadn't been a great deal of widespread national concern with addressing coal mining fatalities. Just three years later, in 1910, the Bureau of Mines was formed within the Department of Interior to specifically deal with the wave of mine disasters that claimed over 30,000 lives in the preceding decade.

The coal industry and its political allies create a smokescreen that does nothing to "protect" jobs. The continuous failure of the coal industry to follow basic laws that protect workers and the environment clearly demonstrates where their priorities lie.

Let's go back to mine safety for a moment. On December 6, 1907, at 10:28 AM, approximately 367 men in two mines were killed in an explosion thought to be caused by either an electrical spark or an open flame lamp that ignited coal dust in the air. Up to that point, there hadn't been a great deal of widespread national concern with addressing coal mining fatalities. Just three years later, in 1910, the Bureau of Mines was formed within the Department of Interior to specifically deal with the wave of mine disasters that claimed over 30,000 lives in the preceding decade.

In 1951, a mine explosion in Illinois killed 111 miners. In response, the Federal Coal Mine Safety Act was signed into law on July 16, 1952. This gave the federal government authorization to conduct annual inspections, and gave the Bureau of Mines authority to shut down a mine if there was perceived "imminent danger." The mining company would face civil penalties if they failed to comply with an order to shut down.

On November 20, 1968, an explosion at Consol No. 9 mine near Farmington, West Virginia trapped 99 miners. 78 people died in the explosion, and 19 bodies were never recovered. The response was the enactment of the Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act of 1969. This created what is now the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA), and required two annual inspections of every surface mine and four at every underground coal mine. It required monetary penalties for all violations and established criminal penalties for willful violations. An understaffed regulatory agency meant that enforcement was slow going, which in turn led to criticism when 38 men were killed in the Hurricane Creek mine disaster the day after the law was passed.

The law, when properly enforced as intended, serves to ameliorate specific problems. However, when the law isn't enforced properly for any number of reasons, the result is a ticking time bomb. Continuing on the topic of mine safety, consider this: On April 5, 2010, a coal dust explosion in Massey Energy's Upper Big Branch coal mine in Raleigh County, West Virginia, killed 38 miners. In 2011, MSHA issued its final report, concluding that major safety violations were a contributing factor to the explosion. The agency issued 369 citations and assessed millions in penalties. Massey Energy CEO was convicted of "conspiring to willfully violate safety standards." Investigators stated that the MSHA (among others) was at fault for failure to act decisively at the mine even after Massey was issued 515 citations for safety violations at Upper Big Branch in 2009.

The independent investigation team issued a report in 2011 on the disaster states that Massey used its power "to attempt to control West Virginia's political system." The report cites that politicians feared the company because it "was willing to spend vast amounts of money to influence elections." It also says that Massey intentionally neglected safety precautions for the purpose of increasing profit margins (source).

On November 20, 1968, an explosion at Consol No. 9 mine near Farmington, West Virginia trapped 99 miners. 78 people died in the explosion, and 19 bodies were never recovered. The response was the enactment of the Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act of 1969. This created what is now the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA), and required two annual inspections of every surface mine and four at every underground coal mine. It required monetary penalties for all violations and established criminal penalties for willful violations. An understaffed regulatory agency meant that enforcement was slow going, which in turn led to criticism when 38 men were killed in the Hurricane Creek mine disaster the day after the law was passed.

The law, when properly enforced as intended, serves to ameliorate specific problems. However, when the law isn't enforced properly for any number of reasons, the result is a ticking time bomb. Continuing on the topic of mine safety, consider this: On April 5, 2010, a coal dust explosion in Massey Energy's Upper Big Branch coal mine in Raleigh County, West Virginia, killed 38 miners. In 2011, MSHA issued its final report, concluding that major safety violations were a contributing factor to the explosion. The agency issued 369 citations and assessed millions in penalties. Massey Energy CEO was convicted of "conspiring to willfully violate safety standards." Investigators stated that the MSHA (among others) was at fault for failure to act decisively at the mine even after Massey was issued 515 citations for safety violations at Upper Big Branch in 2009.

The independent investigation team issued a report in 2011 on the disaster states that Massey used its power "to attempt to control West Virginia's political system." The report cites that politicians feared the company because it "was willing to spend vast amounts of money to influence elections." It also says that Massey intentionally neglected safety precautions for the purpose of increasing profit margins (source).

Coal Industry Pattern and Practice

If the coal industry's mine safety record is any indication of its priorities, it's easy to infer where they lie on issues affecting the environment and people who live and work in the nation's coalfields and beyond.

Coal-related issues include:

While it might be difficult for a coal company to argue against laws to protect workers, especially when mining disasters tend to bring dramatic and widespread backlash against the industry, the types of issues listed above give coal companies and their political allies much more wiggle room. Peter Barth of the University of Connecticut says that a major characteristic of coal mining "is its isolation, both geographically and culturally, from other areas of the nation. Coal is mined, generally, in remote regions that are rarely, if ever, seen by people from the more populated parts of the country." (source) Coal-fired power plants as well as coal waste disposal sites have a severely disproportionate impact on low-income and people of color, who are much more likely to be living nearby.

Isolated and vulnerable communities are virtually steamrolled by the coal industry with little, if any, repercussions. This, of course, is nothing new.

With respect to the environment, the coal industry has a long history of degradation and exploitation. Years of accidents caused by neglect for basic environmental protections took center stage in February of 1972. Logan County, West Virginia experienced particularly heavy rains, and a panicked heavy equipment operator noticed that the upper wastewater impoundment at the Pittston Coal Operation had reached its crest. Soon afterward, the dam failed. This sent over 132 MILLION GALLONS of black wastewater down the hollow in a 30 foot wave that overtook 16 coal towns that lay in its path.

After the waters had subsided, 125 people lay dead, 1, 121 were injured, and over 4,000 were left homeless.

The post-disaster investigation was quite telling, and is yet another lesson in coal's strong political ties. Then-West Virginia Governor Arch A. Moore, Jr. appointed an ad hoc inquiry commission that was made up entirely of coal industry sympathizers or government officials whose complacency contributed to the flood. While the State of West Virginia sued Pittston Coal for $100 million, Governor Arch A. Moore, Jr. allowed a smaller settlement of just $1 million only 3 days before leaving office in 1977.

In response to the flood, there was a backlash in favor of greater environmental protections against the coal industry. As Jimmy Carter Campaigned in Appalachia in 1976, he promised to sign mining regulation bills that would stem the environmental impacts of mining. That promise because a reality on August 3, 1977, as Carter signed a stringent environmental bill, known as the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA), into law.

The idea behind SMCRA is that states will be responsible for establishing their own mining oversight agencies, but those agencies must meet minimum standards set out by SMCRA. Once they have proven that their program meets these standards, the mining oversight responsibility switches over from the federal regulators to the state regulators. The federal regulatory agency established to oversee these programs is the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement (OSMRE). Both the federal law and the federal agency name is a little misleading, because although they do consider "surface mining" issues, they also consider the surface effects of underground coal mining, of which there are many.

Coal-related issues include:

- toxic emissions (particulates, gasses and heavy metals) from mines, power plants, coal processing facilities, coal transportation, and coal waste disposal that affect people as well as the long-term health and viability of ecosystems,

- negative impacts on the landscape, from mining-related forest destruction, groundwater loss, subsidence, farmland destruction, and

- socioeconomic issues that arise from coal's disproportionate impact as a whole on the most vulnerable communities across the country and around the globe.

While it might be difficult for a coal company to argue against laws to protect workers, especially when mining disasters tend to bring dramatic and widespread backlash against the industry, the types of issues listed above give coal companies and their political allies much more wiggle room. Peter Barth of the University of Connecticut says that a major characteristic of coal mining "is its isolation, both geographically and culturally, from other areas of the nation. Coal is mined, generally, in remote regions that are rarely, if ever, seen by people from the more populated parts of the country." (source) Coal-fired power plants as well as coal waste disposal sites have a severely disproportionate impact on low-income and people of color, who are much more likely to be living nearby.

Isolated and vulnerable communities are virtually steamrolled by the coal industry with little, if any, repercussions. This, of course, is nothing new.

With respect to the environment, the coal industry has a long history of degradation and exploitation. Years of accidents caused by neglect for basic environmental protections took center stage in February of 1972. Logan County, West Virginia experienced particularly heavy rains, and a panicked heavy equipment operator noticed that the upper wastewater impoundment at the Pittston Coal Operation had reached its crest. Soon afterward, the dam failed. This sent over 132 MILLION GALLONS of black wastewater down the hollow in a 30 foot wave that overtook 16 coal towns that lay in its path.

After the waters had subsided, 125 people lay dead, 1, 121 were injured, and over 4,000 were left homeless.

The post-disaster investigation was quite telling, and is yet another lesson in coal's strong political ties. Then-West Virginia Governor Arch A. Moore, Jr. appointed an ad hoc inquiry commission that was made up entirely of coal industry sympathizers or government officials whose complacency contributed to the flood. While the State of West Virginia sued Pittston Coal for $100 million, Governor Arch A. Moore, Jr. allowed a smaller settlement of just $1 million only 3 days before leaving office in 1977.

In response to the flood, there was a backlash in favor of greater environmental protections against the coal industry. As Jimmy Carter Campaigned in Appalachia in 1976, he promised to sign mining regulation bills that would stem the environmental impacts of mining. That promise because a reality on August 3, 1977, as Carter signed a stringent environmental bill, known as the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA), into law.

The idea behind SMCRA is that states will be responsible for establishing their own mining oversight agencies, but those agencies must meet minimum standards set out by SMCRA. Once they have proven that their program meets these standards, the mining oversight responsibility switches over from the federal regulators to the state regulators. The federal regulatory agency established to oversee these programs is the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement (OSMRE). Both the federal law and the federal agency name is a little misleading, because although they do consider "surface mining" issues, they also consider the surface effects of underground coal mining, of which there are many.

States take over responsibility for coal mining regulation

|

Over time, many of the states that actively practice coal mining eventually established a state-level program that met SMCRA's standards. These states are referred to as "primacy" states. 24 states have primacy at this time: Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, Colorado, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, New Mexico, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Texas, Utah, Virginia, West Virginia and Wyoming. The only non-primacy state with active coal mining at this time is Tennessee.

To recap: The OSMRE's responsibility in primacy states is to provide oversight of a state's implementation of their regulatory program. "Interestingly," McElfish and Beier state, " the coal industry has always backed state primacy and minimal federal oversight. States and the industry have denounced even weak OSMRE oversight as too strong and intrusive" (Source). |

"the economic importance of the coal industry to at least some of the mining states produces powerful pressures on state legislatures and regulators to accommodate coal interests." McElfish & Beier |

Problems with state oversight

While the concept of state primacy is simple enough, the implications of state-led regulatory oversight is a system wrought with problems. For example, in Pennsylvania (a primacy state), state-level regulations that "technically" meet SMCRA standards nevertheless contain many loopholes that allow the coal industry to cause major environmental problems with little repercussions. This is partly due to regulations that have failed to keep up with rapid changes in mining technology, partly due to lax enforcement from the state's regulatory agency, and partly due to the coal industry's influence that keeps these problems from being fixed.

Neither the coal industry nor the state-level regulators are held accountable for these problems. Exacerbating these issues is the sudden and inexplicable change in the Pennsylvania regulatory agency's practice of holding public meetings in the evening (when most people are able to attend, ask questions and make comments), to the middle of the day, when most people can't take time off work to attend. Any citizen wishing to inform themselves of a coal company's plans has to track down copies of these plans in locations that are always changing and frequently differ from the locations stated in published "Public Notices" in newspapers. This is by no means the extent of the problems in Pennsylvania, or any other coal mining state, but merely an example.

Neither the coal industry nor the state-level regulators are held accountable for these problems. Exacerbating these issues is the sudden and inexplicable change in the Pennsylvania regulatory agency's practice of holding public meetings in the evening (when most people are able to attend, ask questions and make comments), to the middle of the day, when most people can't take time off work to attend. Any citizen wishing to inform themselves of a coal company's plans has to track down copies of these plans in locations that are always changing and frequently differ from the locations stated in published "Public Notices" in newspapers. This is by no means the extent of the problems in Pennsylvania, or any other coal mining state, but merely an example.

A Federal Agency Under Siege

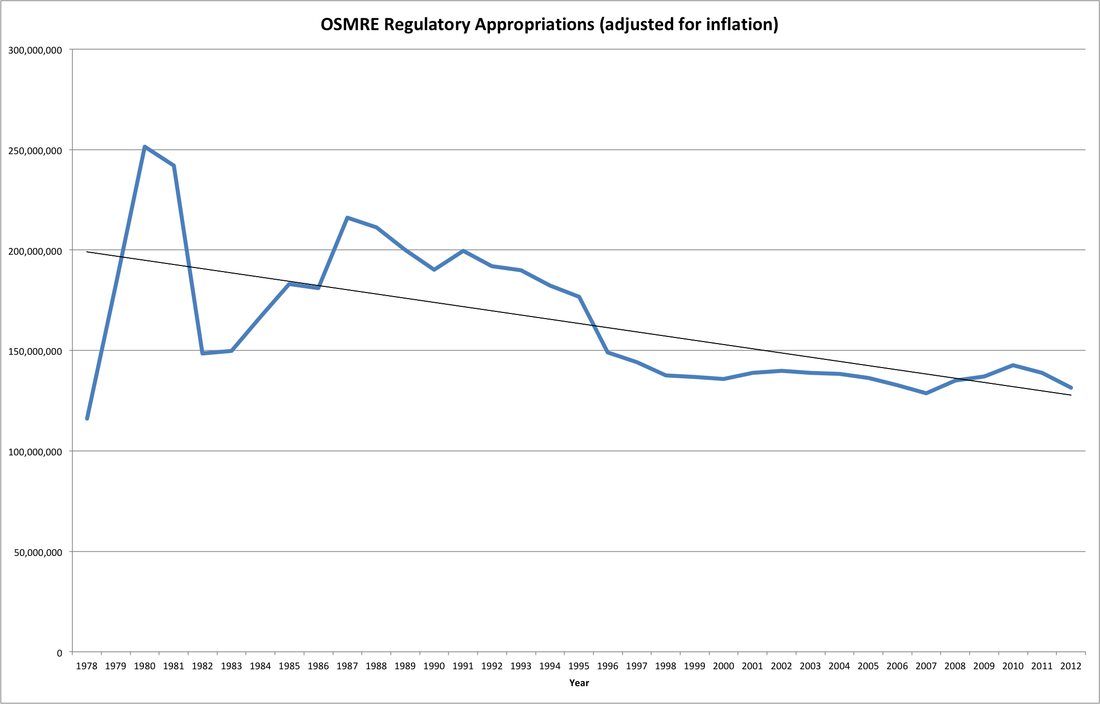

As mentioned earlier, the coal industry is in opposition to the federal agency's role in regulating coal mining. With political allies on the coal industry's side, the OSMRE has faced an onslaught of threats to their regulatory authority. Since the agency's inception, funding for inspections and oversight has decreased dramatically.

Even through a steady increase in coal production, the number of OSMRE mine inspectors remained relatively stable, averaging about 430 total inspectors per year across all coal mining states from 1996-2016. With a steadily decreasing budget, it's surprising that the coal industry would suggest that the regulatory agency would be in any position to wage a "war on coal." Additionally, the average number of coal mines during this same period is 1,356, producing an average of 1,064 thousand short tons of coal per year and employing an average of nearly 79,000 people.

To put this into perspective, the average number of of OSMRE Inspectors responsible for coal mining oversight across all coal mining states is roughly the same as the total number of employees working at two Walmart stores.

The budgetary limitations that restrict the ability of the OSMRE to properly conduct oversight inspections is merely one part of the problem. As citizens approach the OSMRE to request that the agency help fix ongoing problems that they're facing with coal companies in their communities, it's the OSMRE's right and responsibility to ensure that these problems are adequately addressed within the scope of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act. The agency, like other agencies, can issue rules to clear up any confusion and keep the protective nature of the law up-to-date.

For example, the idea of a "coal miner" usually brings to mind a pickaxe and a shovel image of yesteryear. But large machines that mine coal at a mind-boggling rate have largely replaced the coal miner. The breakneck speed of coal production is something that, decades ago, coal companies could have only dreamed about. The rapid evolution of mining technology has come with serious consequences. In the 11 states that practice a form of underground coal mining known as longwall mining, for example, machines carve out so much coal that the water table drops as a result, causing streams, springs and water supplies to dry up. In an effort to help protect against this problem, the OSMRE drafted what was referred to as the "Stream Protection Rule." The Stream Protection Rule would have prohibited coal companies from damaging these water resources, whether by the longwall mining or mountaintop removal.

Nearly immediately after the Trump Administration took office, the carefully and thoughtfully crafted Stream Protection Rule was struck down by the Congressional Review Act, which permits Congress to strike down any actions issued within the previous 60 working days.

To put this into perspective, the average number of of OSMRE Inspectors responsible for coal mining oversight across all coal mining states is roughly the same as the total number of employees working at two Walmart stores.

The budgetary limitations that restrict the ability of the OSMRE to properly conduct oversight inspections is merely one part of the problem. As citizens approach the OSMRE to request that the agency help fix ongoing problems that they're facing with coal companies in their communities, it's the OSMRE's right and responsibility to ensure that these problems are adequately addressed within the scope of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act. The agency, like other agencies, can issue rules to clear up any confusion and keep the protective nature of the law up-to-date.

For example, the idea of a "coal miner" usually brings to mind a pickaxe and a shovel image of yesteryear. But large machines that mine coal at a mind-boggling rate have largely replaced the coal miner. The breakneck speed of coal production is something that, decades ago, coal companies could have only dreamed about. The rapid evolution of mining technology has come with serious consequences. In the 11 states that practice a form of underground coal mining known as longwall mining, for example, machines carve out so much coal that the water table drops as a result, causing streams, springs and water supplies to dry up. In an effort to help protect against this problem, the OSMRE drafted what was referred to as the "Stream Protection Rule." The Stream Protection Rule would have prohibited coal companies from damaging these water resources, whether by the longwall mining or mountaintop removal.

Nearly immediately after the Trump Administration took office, the carefully and thoughtfully crafted Stream Protection Rule was struck down by the Congressional Review Act, which permits Congress to strike down any actions issued within the previous 60 working days.

According to the Center for American Progress, the 27 representatives that sponsored or co-sponsored the Congressional Review Act bill received nearly $500 million from mining interests last year.

With Big Coal so entrenched in politics, it's easy to see that both existing protections must be both preserved and thoroughly enforced, that loopholes exploited by Big Coal need to be closed, and that the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement should be properly funded and staffed with people who have an unwavering commitment to fulfill the spirit of SMCRA.

Burying the OSMRE

In 2011, then-Department of Interior Secretary Ken Salazar made the inexplicable and sudden announcement that there were plans to "fold" the OSMRE into the massive bureaucratic behemoth that is the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). The primary reasoning for the "merger" (which would have essentially amounted to a burial) was to save money. Not only was this proposal illegal according to Section 201 of SMCRA, there were numerous other issues that were problematic: the conflicts between the OSMRE's regulatory duty and the BLM's coal development duties, the isolation of the OSMRE within the BLM would make it more difficult for citizens to oversee the federal government's mining and reclamation responsibilities, and the clear indication that the DOI had a lack of interest in and understanding of the OSMRE's responsibilities to communities, the environment, and coal-impacted citizens.

The plan to bury the OSMRE ultimately failed once it became clear that the supposed cost savings would be minimal, especially in light of the potentially severe impacts that the "merger" would have on coalfield communities.

The plan to bury the OSMRE ultimately failed once it became clear that the supposed cost savings would be minimal, especially in light of the potentially severe impacts that the "merger" would have on coalfield communities.

CCC's Work

Citizens Coal Council is widely considered to be the national go-to organization for matters related to the OSMRE and SMCRA. Our work in promoting government accountability and transparency, with respect to the coal industry, reflects a multi-faceted approach. We believe that citizens that are directly impacted by the mining, processing and use of coal are in the best position to determine the most pressing and urgent matters that they face. We work hard to bring grassroots citizens to the table, and strongly advocate for both transparency in regulatory and legislative decision making in coal-related matters. Likewise, we believe that citizens should be afforded the opportunity to provide meaningful input to regulatory authorities, and that these decisions reflect a thoughtful consideration for vulnerable communities that are impacted by coal.

Among CCC's Transparency and Accountability Activities Include:

Among CCC's Transparency and Accountability Activities Include:

- A legal training on the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA), held over a 3-day period, which was led by 7 attorneys with comprehensive expertise in the law. The training was open to all regardless of ability to pay, and was attended by nearly 80 participants representing all coalfield regions of the United States. This training helped equip participants with in-depth knowledge of the law, and the role of the OSMRE in its enforcement.

- Several in-person, sit-down meetings with the Director of the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement, attended by grassroots citizens from across the country, which afforded these citizens the opportunity to openly and frankly discuss coal-related problems that they experience in their community and ask questions of the Director.

- A sit-down, in person meeting with Department of Interior Secretary Sally Jewell, in which coalfield citizens could discuss their coal-related issues with the newly-appointed Secretary and establish the groundwork for continuing meaningful dialogue.

- Organizing "Ask the Director" meetings, which were attended both in person and via conference calls in several locations across the country. As implied by the name of the meetings, these were opportunities for grassroots coalfield citizens to ask general or specific questions of the OSMRE Director so that they could better understand the role of the OSMRE, the scope of SMCRA, and the status of specific coal-related issues within their community.

- Closely monitoring actions that may potentially affect the OSMRE or the OSMRE's ability to exercise its regulatory authority, and taking action as needed to protect the agency and its authority. We are able to quickly and effectively mobilize a large network of allies to take strategic action.

Additional articles and resources

|

"A 40 Year-Old Law Literally Changed the Appalachian Landscape" (100 Days in Appalachia)

CCC and Kentucky Resources Council joint press release: "40 Years Later: 1977 Landmark U.S. Coal Mining Environmental Law Still Under Threat" |

"The environmental impacts of mountaintop removal mining and other forms of strip mining might be worse without SMCRA, but ...the lack of enforcement by states has severely undercut the law’s effectiveness. A federal investigation released in February, for example, found that West Virginia was lax in enforcement; a week later, Governor Jim Justice criticized state environmental regulators, not for failure to enforce federal laws but for dressing too casually."

|