Across the United States, longwall coal mining has reshaped landscapes, disrupted waterways, and placed entire communities at risk, all while operating under regulatory systems that often fail to keep pace with the scale and speed of modern extraction. Nowhere is this more evident than in Pennsylvania, the only state that requires a recurring, statewide assessment of underground mining damage. Over the past 25 years, Pennsylvania’s Act 54 reports- intended to measure the real-world impacts of longwall mining- have become a record not of responsible oversight, but of mounting environmental losses, fragmented data, and chronic regulatory shortfalls.

Citizens Coal Council has spent more than a decade analyzing these reports, submitting technical comments, and documenting the lived experience of communities on the front lines. Taken together, this body of work shows a clear pattern: longwall mining causes widespread, predictable damage, yet the agencies responsible for protecting streams, homes, and public safety often lack the tools or the political direction to act effectively.

Our analyses of multiple Act 54 evaluations reveal the same core concerns repeating across decades. Early reviews highlighted how state agencies were failing to track all mining-related impacts, leaving much of the damage undocumented and unaddressed. Later assessments deepened the picture: collapsing streams, long-delayed repairs to homes and wells, inconsistent permit reviews, and a regulatory system struggling to fulfill its own mandate.

Even in the most recent assessments, the disconnect between what communities experience on the ground and what appears in official records remains profound. In several comment filings, we raised alarms that essential pre- and post-mining water data often never reaches the programs responsible for reporting water quality conditions to the U.S. EPA, a gap that masks the true scale of mining-related degradation.

Our work has also examined how longwall mining permits are reviewed in practice. Case studies show that environmental risks are frequently underestimated or brushed aside, even in watersheds known to support high-quality aquatic life. We have consistently urged agencies to strengthen protections for vulnerable streams, evaluate whether high-quality waters deserve “special protection” status, and adopt more rigorous monitoring to prevent irreversible losses.

Repeated analyses of Pennsylvania’s permitting and enforcement patterns demonstrate that impacts which regulators once believed could be “predicted and promptly repaired” have instead accumulated into a long-term burden that falls squarely on residents, landowners, and ecosystems.

These Pennsylvania lessons matter far beyond state lines. Longwall mining is used across the country, from the Illinois Basin to the Rocky Mountain West, yet most states do not produce anything like an Act 54 assessment. Without transparent, statewide reporting, mining impacts often remain invisible to the public, policymakers, and even regulators themselves. What Pennsylvania shows through years of reports, community testimony, and independent reviews is that longwall mining consistently damages the land and water that communities depend on, and that meaningful oversight requires much more than permit paperwork or company assurances.

As federal agencies such as the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement (OSMRE) evaluate whether state programs are truly protecting people and the environment, the Pennsylvania experience should serve as a cautionary guide. In our comments to OSMRE, we have urged the agency to take Act 54 data seriously, to confront the failures documented over decades, and to hold state agencies accountable to the core promise of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act: to balance mining with the protection of society and the environment.

As federal agencies such as the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement (OSMRE) evaluate whether state programs are truly protecting people and the environment, the Pennsylvania experience should serve as a cautionary guide. In our comments to OSMRE, we have urged the agency to take Act 54 data seriously, to confront the failures documented over decades, and to hold state agencies accountable to the core promise of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act: to balance mining with the protection of society and the environment.

Longwall mining has taught us, again and again, that the impacts are real, measurable, and lasting. Communities deserve regulatory systems that acknowledge those truths and act on them. By understanding the lessons of Pennsylvania’s longwall legacy, states and federal agencies have an opportunity and an obligation to prevent the same harms from continuing unchecked across the nation.

A Plain-Language Guide for Communities

For people new to longwall mining, we created Longwall Mining A to Z (2016)– a clear, accessible guide explaining the mining method, its impacts, the regulatory system, and what communities can expect.

The Arc of Act 54: 25 Years of Findings

Pennsylvania is the only state that requires a recurring, five-year review of underground mining damage. Over time, these Act 54 reports have become a window into the cumulative effects of longwall mining: stream losses, structural damage, delayed repairs, and gaps in regulatory oversight. For a deeper look at how these impacts have unfolded over a quarter-century, see our analysis, Undermining Trust: The Collapse of Environmental Protection in Pennsylvania (2021).

How Today’s Failures Echo the Past

Many of the problems communities face today- untracked stream impacts, incomplete water data, and inconsistent permitting- were identified years ago. Earlier assessments, including our review of the 2011 Third Act 54 Report, documented fundamental shortcomings in how impacts were recorded and analyzed. These issues remain largely unresolved, shaping the challenges residents still confront.

Permitting Decisions That Shape the Future

Longwall mining permits are often approved based on optimistic predictions about environmental risk. Our case study, The Illusion of Environmental Protection (2014), examined the Foundation Mine application and revealed how permitting can underestimate the true scale of potential damage to streams, wetlands, and landowners.

When Water Quality Data Goes Missing

Our comments to Pennsylvania DEP in 2022 highlighted a significant problem: water data collected by mining companies and DEP’s own mining program often never appears in the state’s official water quality reports to EPA. This disconnect hides the full picture of mining-related impacts.

Federal Oversight: A Call for Accountability

In 2022, we urged the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement to conduct a meaningful evaluation of Pennsylvania’s longwall mining program- one that accurately reflects the damage documented in Act 54 reports. Our comment letter explains why federal scrutiny is long overdue and how national oversight can better protect communities.

Protecting High-Quality Streams Before It’s Too Late

Not all waterways receive the protections they deserve. Our technical analysis from 2010 showed that several streams in Greene and Washington Counties met the criteria for “Special Protection” status, yet had never been properly surveyed by regulators. These gaps matter, because once longwall panels pass beneath a high-quality stream, restoration becomes far more costly, if it’s possible at all.

What Communities Are Seeing on the Ground

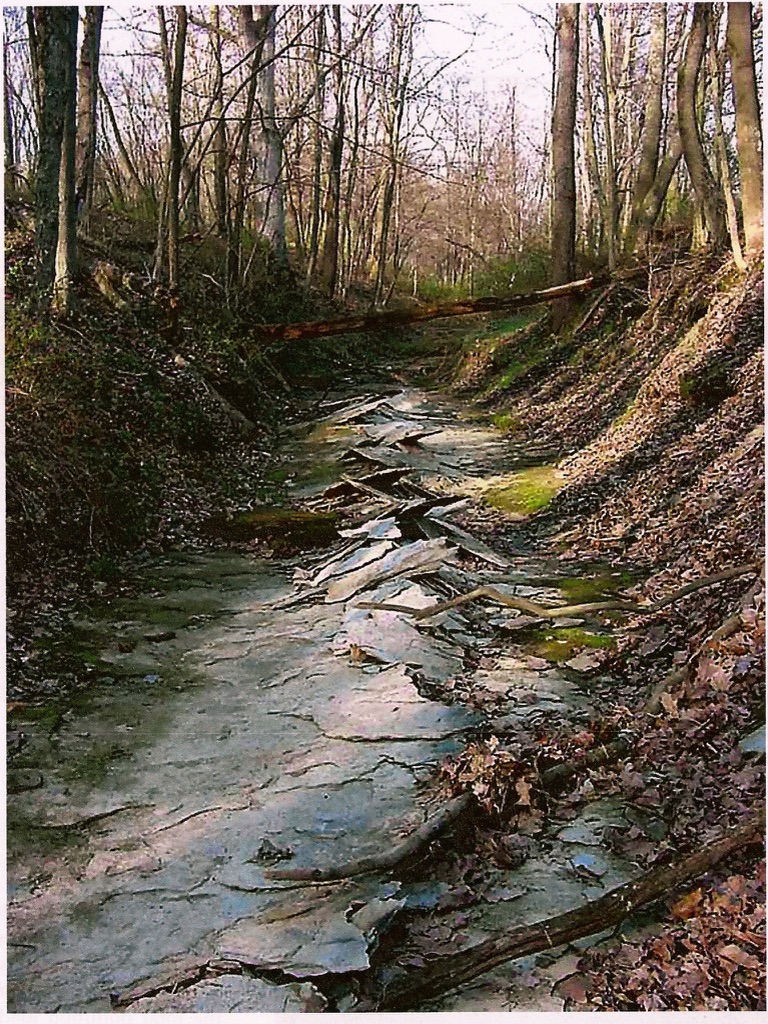

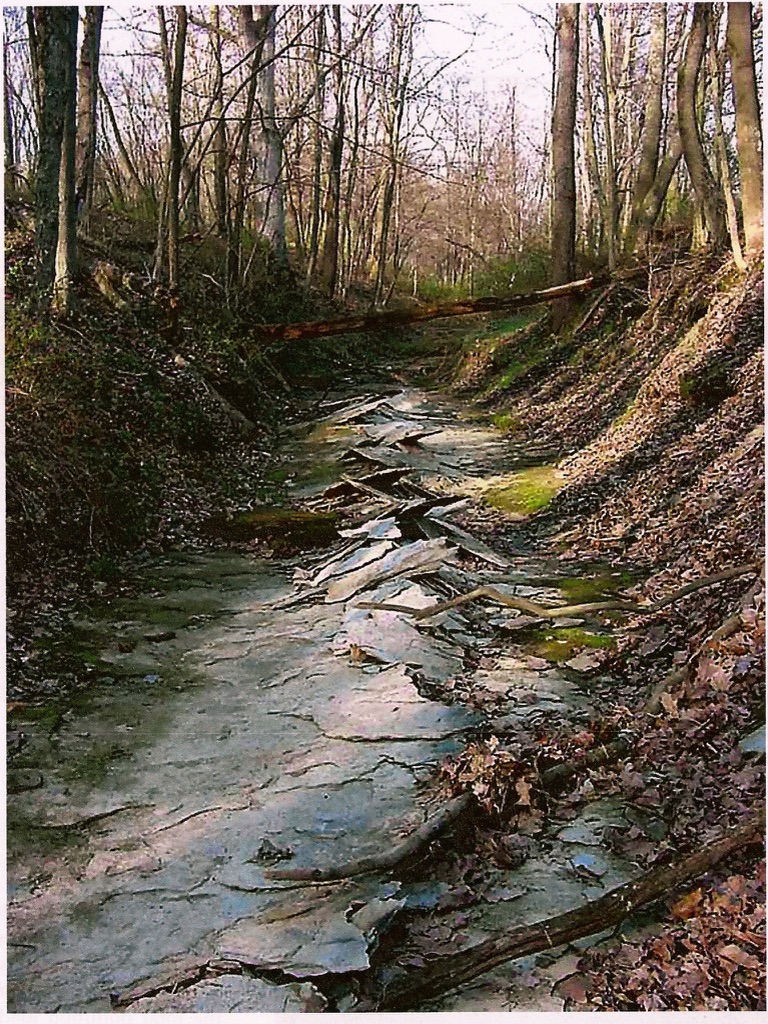

Residents have long reported disappearing springs, sinking land, and streams that never recover after longwall panels pass underneath. Our 2010 report, Protection of Water Resources from Longwall Mining Needed in Southwestern Pennsylvania, places these stories in the broader context of state regulatory practices and enforcement challenges.

Stream Protections on Paper vs. Reality

Pennsylvania’s laws are supposed to prevent mining from destroying streams- but our 2017 report shows that the system is still failing too many waterways. Field investigations documented streamflow losses, habitat decline, and delayed or incomplete remediation efforts. The report concludes that without stronger enforcement and more transparent data, communities bear the brunt of mining damage while streams continue to degrade. Aligning regulations with real-world science is critical for safeguarding water resources.